***Coming Soon***

Sunday, May 31, 2015

Sunday, May 24, 2015

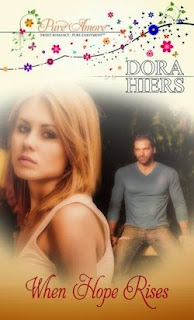

When Hope Rises by Dora Heirs

Keep your lives free from the love of money and be content with what you have, because God has said, “Never will I leave you; never will I forsake you.” Hebrews 13:5

What about “no” couldn’t the hulk understand? Shelby Coltman grimaced and lowered her head, ducking through the first door on the right. Not that she could do anything to disguise her thick veil of apricot hair or pale complexion.

The normally bustling hall of Beaver Pond High School was deserted this late in the afternoon.

She could only hope the football coach didn’t see her. With her back pressed against the door, she closed her eyes and listened to the footsteps echo in the quiet corridor, the electronic tablet clutched to her chest. Please keep going. Don’t stop. She needed to have a heart-to-heart with the burly coach. It was only early February. She couldn’t dodge him for the rest of the school year.

“Make it a habit to visit the men’s restroom, Ms. Coltman?” The amused voice, velvety and deep, cut through her admonition.

The men’s bathroom?

Her head popped up, along with her eyelids. Her nose verified her location. Ammonia and citrus collided. She wrinkled her nose, glancing at the sinks, stalls, urinals, and…Tate Malone.

The guy she always wanted to see. Except in the men’s bathroom. She winced and her words came out squeaky. “Only when I know you’re in here.”

Heavy dark brows lifted over warm, cinnamon-tinted eyes, and he continued wiping his hands on the paper towel, but other than that, he didn’t respond to her teasing. He never did. Her attempts to get him to open up only made him tighten that cloak of reserve.

Unlike the coach who kept spewing unwelcome date invites.

Sighing, she loosened her chokehold on the tablet, her arm dropped to her side. “Coach Joe’s out there. I didn’t want to run into him.”

Tate nodded. One slow, long, knowing look.

Did he not believe her?

“It’s really not what it sounds like. He’s asked me out and I’ve told him no, especially after I heard about his reputation.” Shelby shuddered. A guy like that just didn’t line up with her purity vow. “He’s definitely persistent. Probably what makes him such a good football coach. I can’t seem to make him understand that I don’t want to go out with him, but the school hallway just doesn’t seem like the right place for that conversation.” She could just hear what Tate didn’t say.

So the men’s bathroom was a better spot?

Why was she babbling to a guy who didn’t care about her not wanting to date the coach? She pinched the bridge of her nose. How did she get herself into these situations?

“Come on.” Tate flicked the towel in the trashcan and cupped her elbow.

“W-w-where?”

“Let’s take care of this situation right now. Before it turns ugly.” Determination lined Tate’s lips as he opened the door. Why did he look as if he was upset with her? “I know just the right place for this discussion. The principal’s office.”

She was being sent to the principal’s office again? Memories of her high school years flooded back. The principal’s repeated warnings to stop daydreaming in class and start paying attention, or she’d risk not graduating. Shelby closed her eyes and groaned. If the principal canned her, she might never be able to open her storefront.

“It’ll be OK.” Tate reassured.

His brief touch on her arm was enough to propel her into the hallway, squeezing through the opening, catching a whiff of Tate’s clean, woodsy smell. Close enough to feel irritation vibrate from Tate’s limbs, to hear the pressure in the hitch of his breath.

She licked dry lips as Tate followed her into the hallway.

“Hey, Joe, wait up.”

The hulk turned. Heavy brows hiked up, and then narrowed when he spotted Shelby standing next to Tate. His gaze shot to the sign above the men’s bathroom. Scorn gleamed from his eyes as they made a slow trip from her chest to her legs and back again.

She tucked the tablet against her blouse.

The giant sneered. “I didn’t know you two were an item.”

Shelby sucked in a breath “What? We’re not—”

Joe’s gaze speared her mid-section.

She glanced down. Tate’s fingers were curled around her arm. When did that happen?

“Coach, Ms. Coltman and I are headed to Principal Winecoff’s office. I thought you might like to join us.” Tate didn’t move his hand.

“Why?” The coach practically snarled.

“Because we’ll be discussing sexual harassment.” Tate’s tone was firm, and although the burly coach had about a hundred pounds on him, Tate never flinched or backed down from the big man’s glare.

“Thanks, but I have better things to do with my time.” Coach Joe whirled and stalked away.

Claiming sexual harassment?

Dread boiled in her belly. That sounded like the kiss of death for her teaching career at Beaver Pond. And her dreams of opening her store, From Junk to Treasure.

Shelby turned to Tate, the man responsible for the demise of her dreams. She wanted to be mad at him, so she avoided his cinnamon-flecked eyes, choosing to focus on the mole just below his cheek. Next to his lips.

Big mistake. “W-we are?”

“Yeah.”

“But why? The words ‘sexual harassment’ never came out of my mouth.”

“They didn’t have to.” His fingers curled around her arm again, guiding her towards the administrative office.

Shelby gulped. “Tate, I appreciate what you’re trying to do, but I can’t afford to lose my job.”

“You won’t lose your job, Shelby. Trust me.”

Trust him?

She’d heard those words before. A few times from her ex-boyfriend. When he wanted something precious that she wasn’t willing to give. Could she trust Tate? Or was he just like all the other guys she’d dated?

~*~

Why was she so worried about losing her job? She didn’t need it. Not like he did, or the countless other teachers who supported families and barely survived from one paycheck to the next.

She cast a worried look in his direction. “But—”

“You said Coach doesn’t take ‘no’ for an answer, right?”

Long apricot locks rippled against her shoulders as her pretty head wobbled.

“I don’t want this situation to escalate into something much worse.” Or to risk her being hurt by the heartless jock. Not that he’d mention that.

They reached the administration office. The place was dark, except for the principal’s office, and the only sound was the occasional chatter of the custodians over the radio. Tate rapped lightly on the door.

“Come in.” The heavy door muffled the principal’s response.

Shelby’s fingers pressed lightly against his hand on the doorknob. Her head tilted at an angle, desperation clouding her expression.

“Shelby, I can’t not report this.”

Her head dipped to her chest.

He nudged her chin up with a thumb and found himself gazing into beautiful blue eyes, as clear and pristine as a cloudless North Carolina sky. He breathed deep, but all he could smell was an alluring combination of roses and some kind of citrus. He exhaled and vowed not to breathe until more than a couple of feet separated them.

He’d managed to keep a healthy distance between them for the entire first semester of staff meetings. This was the closest he’d gotten to Shelby, and he didn’t like it. Didn’t welcome the intense longing that hummed through his body from being so close to her. Didn’t appreciate how being around her awakened the dreams of family, the possibility of a forever love that he’d squashed to oblivion along with his parents’ desertion fourteen years ago. No. Those dreams were best left dormant.

Shelby Coltman was born into wealth, obvious from the expensive car she drove, the elegant clothes she wore, the perfectly straight teeth and flawless complexion. Even her exquisite creations.

He made it a point to wander past her classroom every afternoon on his way to the parking lot and peek in at her artwork.

She couldn’t possibly know what it felt like to move twenty times during one year, to be yanked from one school after another. To wear the same clothes to school day after day because that was the only set of pants he owned. Or to lug a bucket to the park at night to transport water home so his sister could bathe because their water had been disconnected. Or to carry toothpaste and shampoo because he never knew when he might have the opportunity to wash. Or to sleep in their coats because the electricity had been cut off for non-payment. His life had been ugly.

Until God cleaned it up.

No. He had nothing in common with the pretty art teacher. Shelby would never understand the poverty he came from. Not that he wanted her to, but he’d do well to remember they came from two completely different worlds. His frustration came out in a huff. “Hey. It’ll be OK.”

She nodded, resignation drooping her shoulders.

What was she so upset about? Didn’t she say she wanted to put an end to the coach’s unwanted advances?

So did Tate. He didn’t want to see her fall for Joe’s charm like the countless other females who’d succumbed to muscles and ego. But if he were truthful, it was more than that. He didn’t like the way Joe looked at Shelby, the way he leered at her. Tate wasn’t willing to risk her safety. If that meant keeping tabs on her to see that she was safe, he intended to do just that.

He pushed the door open and gestured for Shelby to enter first. She slid past him, and he got another whiff, this time of her hair. She was all about berries and springtime. Dreams and…forever. She made him think about the future.

OK. Maybe it would be best if he kept tabs on her from a distance.

“You guys are working late.” Principal Winecoff looked up from the paperwork sprawled across his desk, his reading glasses hanging low on his nose. He scratched his balding head and removed his specs. The chair squeaked as he leaned back. “Have a seat.”

Shelby settled in the chair, her tongue sliding out to lick her lips.

Tate lost his train of thought.

“What can I do for you?”

Tate flicked his attention back to the principal and sank into the other chair. “Shelby’s experiencing an issue with Coach Joe.”

Understanding hardened the Principal’s face. He scrubbed a hand across his jaw and shot forward, his chair emitting another obnoxious screech. “I see.”

“It’s not really a problem—”

“He keeps asking her out after she’s refused his invitation to the point where she’s avoiding him.” Tate interrupted.

“That is a problem then, Ms. Coltman.” The principal pulled a desk drawer, tugged out a note pad, and slid it on the desk. “We will not tolerate bullish behavior, especially if it borders on sexual—”

Shelby gave her head a vigorous shake. “I wouldn’t call it by that name, Mr. Winecoff. I’m sure once we have a heart-to-heart, Coach Joe—”

“How about if I have a chat with him?” The principal said, jotting some notes on the paper. “And remind him of the consequences of this type of behavior.”

“I really don’t want to get him in any trouble…” Shelby nibbled on her fingernails and shot Tate a glare as close as her pretty face could come to a glower.

Tate bit back a grin.

“Coach Joe makes enough trouble for himself. You’re not responsible. Now, you be sure to let me know if this continues to be a problem, you hear?” Principal Winecoff stood.

That was their cue that the meeting was over.

“All right.” Shelby didn’t look as if it was all right. Anything but.

Tate followed her to the door. He opened it and gestured for her to go first, trying not to breathe, or grin, while she stalked past. Her shoulders pressed back and fire shot from her glare.

The principal halted his progress with a hand to Tate’s shoulder. “Tate, would you mind keeping a close eye on this situation for me? A rather discreet eye.”

“Sure.” He’d planned to. The principal didn’t need to ask.

“Thank you. I’m not sure I trust Ms. Coltman to let me know if the situation continues.”

“Yeah. Me, either.”

Shelby was too sweet, too naïve for her own good. None of the ladies had refused Coach Joe before. He might not take rejection well. Coach Joe was blunt. Tate wouldn’t put it past him to sling hateful words.

Much like Tate’s last girlfriend. Decent and sweet enough until he refused her advances. Then, she’d called him a “freak” and quite a few other vile names.

Yeah. He’d look out for Shelby, but he’d do his best to avoid her and the tender, protective feelings she evoked in him.

Sunday, May 17, 2015

The Art of Losing Yourself by Katie Ganshert

Prologue

Carmen

The nurse rolled me down a hallway and through a door where my husband waited on a chair pushed into one corner of the small recovery room. He stood as soon as we entered.

“She’s pretty groggy, but she’s awake. She has to be up and walking before y’all can go.”

“Is she in any pain?” Ben asked.

I closed my eyes, feigning sleep.

“She shouldn’t be.”

The door closed.

Ben came to my bedside and wrapped my cold, lifeless hand in his strong grip, as if the tighter he held, the closer I’d stay. But it was too late. I was already gone.

When the nurse returned, Ben stepped back. She gently shook my shoulder, encouraged me to sit, then stand, then walk across the room. And just like that, they released me—as if getting up and walking meant I was all better now.

Ben hovered as we made our way outside, his stare heating the side of my face more intensely than the Florida sun. He hadn’t stopped looking at me since the nurse rolled me into that room. I had yet to look at him. He opened my car door. I eased inside, pulled the seat belt across my chest, and stared straight ahead with dry eyes and an empty heart. As soon as he turned the key in the ignition, Christian music filled the car.

Like a viper, my hand struck the power button.

We drove in silence.

Unable to get warm, I wrapped my arms around my middle and watched the palm trees whiz past the window in streaks of vibrant green. Ben white-knuckled the steering wheel, darting glances at me every time we hit a red light. When he pulled into the driveway of our home, neither of us moved. We sat in the screaming silence while I drifted further and further away—out into a sea of drowning hopes.

“Carmen.” An entire army of emotions marched inside the confines of my name, desperation leading the way.

A better wife might have met her husband halfway, might have even offered him some reassurances—a glance, a hand squeeze, some sign that all would be well. I could do nothing but gaze at the pink blossoms on the crepe myrtle in our front lawn. New life.

How ironic.

Ben reached across the console and set his hand on my knee. “Tell me what to do. Tell me how to make this better.”

Something feral clawed its way up my throat. A baby would make this better. Give me a baby.

Ben and I did everything right. We did things God’s way. So why wasn’t this happening? Why did this continue to happen? But I swallowed the wild thing down and moved my leg.

His hand slid onto the seat—bereft and alone.

Gracie

When you grew up in a small town like New Hope, Texas, obscurity was a luxury that didn’t exist. I was the daughter of Evelyn Fisher, a woman known for two things—making frequent visits to the corner liquor store and baptizing herself in the creek every other Sunday.

My little-girl self would sit on the tire swing beneath our oak tree, my big toe tracing circles in the dirt, and watch as my mother crossed herself in the name of the Father, the Son, and the Holy Ghost before walking out into the water that bordered our backyard. I remembered being more puzzled by the crossing than the actual baptizing. Back then, we went to a Baptist church where folk didn’t do that sort of thing.

“You can take the girl out of the Catholic, but you can’t take the Catholic out of the girl,” she’d say.

“I don’t know what that means.”

“It means old habits die hard, Gracie-bug.”

That, I understood. Because as often as she emptied her bottles into the sink and dunked herself in that creek, the liquor cabinet never remained empty for long. Needless to say, we were odd ducks in New Hope, and the oddest ducks of all at our church. Not so much because Mama carried a rosary in her purse, or cried during the sermons, or crossed herself during the benediction, but because she drank, and according to our pastor, drinking was the same as dancing with the devil.

One Sunday, as she headed toward our small house, soaking wet from head to toe, I stopped my tire-spinning and squinted at her through the afternoon brightness. “Why do you dunk yourself into the creek like that?”

She paused, as if noticing me for the first time. That happened a lot—her forgetting I was around. Usually I had to go and get into some real trouble in order to remind her. Mama brought her hand up to her forehead like a visor. “To be made new, baby girl.”

Eventually, she gave up on the baptizing and decided on rehab instead. I was at the end of fourth grade when she dropped me off at my father’s for three months. When she finally picked me up, all of our belongings were crammed into the back of our rusty station wagon. We left New Hope behind and drove east to the town of Apalachicola, Florida. Mom got a job as a waitress and I went to school at Franklin County. No more church. No more creek-dunking. The one thing that hadn’t changed? Mama’s dance with the devil.

At the sound of my alarm, I experienced a wave of two diametrically opposed emotions. Relief, because this was my final year of high school at Franklin. And dread, because this was only the first day.

I slapped my phone into silence and picked up the mood ring on my nightstand, its stone the color of stormy sky. I didn’t actually believe it could read my mood, but I found it beneath a Laffy Taffy wrapper in one of the many roadside ditches I delittered over the summer. It was actually a nice ring, made with legit silver—not like those cheesy five-dollar ones you find at chintzy stores like Claire’s. Plus, it fit. So I cleaned it off and stuck it in my pocket. My single, solitary treasure from a summer filled with trash.

Muffled conversation filtered through the sliver of space between the worn carpet and my bedroom door—a female-male exchange about a water main breaking in downtown Tallahassee. Mom was either (a) already awake watching the news or (b) passed out on the couch from the night before with the TV still on. If I had any money to bet, I’d put it all on option b.

I pressed my thumb over the mood ring’s stone and pictured violet—a color that meant happy, relaxed, free. I knew because last spring, I’d found this behemoth paperback at Downtown Books titled The Meaning of Color and read it in a single day. I removed my thumb from the stone and took a peek. The amber color of a cat’s eye stared back me—mixed emotions.

Maybe the ring worked after all.

With a resigned sigh, I kicked off the tangle of sheets covering my legs and poked my head outside the door. The TV cast a celestial glow on my mother, who lay sprawled on the couch, one arm flung over her head. Dead to the world.

One hundred eighty days…one hundred eighty days…one hundred eighty days…

This became my mantra as I brushed my teeth, rinsed my face, lined my eyes with liquid liner, and dressed in a simple tee, frayed jeans, and a pair of combat boots I had purchased at a consignment shop back when I still had money. Thanks to Chris Nanning and my bad decision and the fat judge with a chronic scowl, my bank account had been wiped clean. I checked my reflection one last time.

The faded postcard I kept wedged in the corner of my dresser mirror had come loose. I pulled it all the way out and flipped it over. The invitation on the back was equally faded, but sharp and clear in my mind. It was the only place where my company wasn’t just tolerated, but requested. Desired, even. If the evidence wasn’t there, staring me in the face, I’d probably chalk the memories up to a serious case of wishful thinking.

I rewedged card back into place and tucked a strand of coal-colored hair behind my ear. It didn’t stay. Two days ago, in a moment of impulsivity, I chopped off my hair and dyed it black. At the time, the change had felt bold, symbolic even, like a thumbing of my nose at the student body, which would undoubtedly be whispering behind my back extra loud on the first day of school. The new do was my message to them that I didn’t care what anyone said or thought.

If only that were true.

In the kitchen, an empty bottle of wine stood at attention on the counter; another lay tipped on its side in the basin of the sink. I grabbed a strawberry Pop-Tart from one of the cupboards and glanced at the clock. Seven forty-five.

“Mom!” I turned on the faucet and slurped in a drink from the running water, then snagged my school bag from the back of a chair in the dining room. “It’s time to go.”

She mumbled something incoherent.

I picked up the remote from the coffee table and shut off the female news anchor. “You need to get ready.”

She wiped at a string of drool and rolled over. Even with the smudged mascara, the tangled mat of hair, the angry red crease running the length of her cheek, she managed to pull off beautiful. Too bad for me, I took after my father.

“I’m gonna be late for school. And you’re gonna be late for work.”

“Too tired,” she croaked.

More like too hung over.

Heat stirred in my chest. I took a deep breath and exhaled. I had no idea how many more times she could be late before she got the ax, but my mother’s tardiness wasn’t my problem. It would only become my problem if I stayed here. Her boss might extend some grace; Principal Best (a name too ironic for words), on the other hand, would not. I dug inside her purse and grabbed her keys.

One hundred eighty days…one hundred eighty days…one hundred eighty days…

Sunday, May 10, 2015

The Wood's Edge by Lori Benton

August 9, 1757

A white flag flew over Fort William Henry. The guns were silent now, yet the echo of cannon-fire thumped and roared in the ears of Reginald Aubrey, officer of His Majesty's Royal Americans.

Emerging from the hospital casemate with a bundle in his arms, Reginald squinted at the splintered bastion where the white flag hung, wilted and still in the humid air. Lieutenant Colonel Monro, the fort’s commanding officer, had ordered it raised at dawn — to the mingled relief and dread of the dazed British regulars and colonials trapped within the fort.

Though he'd come through six days of siege bearing no worse than a scratch — and the new field rank of major-beneath Reginald's scuffed red coat, his shirt clung sweat — soaked to his skin. Straggles of hair lay plastered to his temples in the midday heat. Yet his bones ached as though it was winter, and he a man three times his five-and-twenty years.

Earlier an officer had gone forth to hash out the particulars of the fort's surrender with the French general, the Marquis de Montcalm. Standing outside the hospital with his bundle, Reginald had the news of Montcalm's terms from Lieutenant Jones, one of the few fellow Welshmen in his battalion.

"No prisoners, sir. That's the word come down." Jones's eyes were bloodshot, his haggard face soot-blackened. "Every soul what can walk will be escorted safe under guard to Fort Edward, under parole ..."

Jones went on detailing the articles of capitulation, but Reginald's mind latched on to the mention of Fort Edward, letting the rest stream past. Fort Edward, some fifteen miles by wilderness road, where General Webb commanded a garrison two thousand strong, troops he’d not seen fit to send to their defense, despite Colonel Monro’s repeated pleas for aid — as it seemed the Almighty Himself had turned His back these past six days on the entreaties of the English. And those of Reginald Aubrey.

Why standest thou afar off, O Lord?

Ringing silence lengthened before Reginald realized Jones had ceased speaking. The lieutenant eyed the bundle Reginald cradled, speculation in his gaze. Hoarse from bellowing commands through the din of mortar and musket fire, Reginald’s voice rasped like a saw through wood. “It might have gone worse for us, Lieutenant. Worse by far.”

“He’s letting us walk out of here with our heads high,” Jones agreed, grudgingly. “I’ll say that for Montcalm.”

Overhead the white flag stirred in a sudden fit of breeze that threatened to clear the battle smoke but brought no relief from the heat.

I am feeble and sore broken: I have roared by reason of the disquietness of my heart —

Reginald said, “Do you go and form up your men, Jones. Make ready to march.”

“Aye, sir.” Jones saluted, gaze still fixed on Reginald’s cradling arms. “Am I to be congratulating you, Capt — Major, sir? Is it a son?”

Reginald looked down at what he carried. A corner of its wrappings had shifted. He freed a hand to settle it back in place. “That it is.”

All my desire is before thee; and my groaning is not hid from thee—

“Ah, that’s good then. And your wife? She’s well?”

“She is alive, God be thanked.” The words all but choked him.

The lieutenant’s mouth flattened. “For myself, I’d be more inclined toward thanking Providence had it seen fit to prod Webb off his backside.”

It occurred to Reginald he ought to have reprimanded Jones for that remark, but not before the lieutenant had trudged off through the mill of bloodied, filthy soldier-flesh to gather the men of his company in preparation for surrender.

Aye. It might have gone much worse. At least his men weren’t fated to rot in some fetid French prison, awaiting ransom or exchange. Or, worst of terrors, given over to their Indians.

My heart panteth, my strength faileth me—

As for Major Reginald Aubrey of His Majesty’s Royal Americans . . . he and his wife were condemned to live, and to grieve. Turning to carry out the sentence, he descended back into the casemate, in his arms the body of his infant son, born as the last French cannon thundered, dead but half an hour past.

The resounding silence brought on by the cease-fire gave way to a tide of lesser noise as soldiers and civilians made ready to remove to the entrenched encampment outside the fort, hard by the road to Fort Edward. There the surviving garrison would wait out the night. Morning promised a French escort and the chance to put the horrors of William Henry behind them.

All thy waves and thy billows are gone over me—

Reginald Aubrey ducked inside the subterranean hospital, forced to step aside from the path of a surgeon spattered in gore. The balding, sweating man drew up, recognizing him. “Your wife, sir. Best wake her and judge of her condition. If she cannot be moved . . . well, pray God she can be. Those who cannot will be left under French care, but I’d not want a wife of mine so left—not with the savages sure to rush in with the officers.”

“We neither of us shall stay behind.” Reginald turned a shoulder when the surgeon’s gaze dropped to the still bundle.

He’d been alone with his son when it happened. Spent after twenty hours of wrenching labor, Heledd had barely glimpsed the child before succumbing to exhaustion. She’d slept since on the narrow cot, the babe she’d fought so long to birth nested in the curve of her arm. Craving the light his son had shed in that dark place, Reginald had returned to them, had come in softly, had bent to admire his offspring’s tiny pinched face, only to find the precious light had flickered and gone out.

A hatchet to his chest could not have struck a deeper blow. He’d clapped a hand to his mouth, expecting his life’s blood to gush forth from the wound. When it hadn’t, he’d taken up the tiny body, still pliable in its wrappings, and left his sleeping wife to wander the shadowed casemate, gutted behind a mask of pleasantry as those he passed offered weary felicitations, until he’d met Lieutenant Jones outside.

How was he to tell Heledd? To speak words that would surely crush what remained of her will to go on? These last days, trapped inside a smoking, burning hell, had all but undone her. And it was his fault. He’d known . . . God forgive him, he’d known it the day they wed. She wasn’t suited for a soldier’s wife. He ought to have left her in Wales. Insisted upon it. But thought of being an ocean away from her, likely for years . . .

Born an only child on a prosperous Breconshire estate not far from his own, Heledd had been raised sheltered, privileged. Reginald had admired her from afar since he was a lad. She’d taken notice of him by the time she was seventeen. Six months later Reginald, twenty-three and newly possessed of a captain’s commission, had proposed.

When it came time for them to part, Heledd had begged. She’d pleaded. She’d made all manner of promises. She would follow the drum as a soldier’s wife. He would see how brave she could be.

She’d barely weathered the sea voyage. The sickness, the filth, the myriad indignities of cramped quarters had eaten away at her fragile soul, leaving behind a darkness that spread like a stain, until he barely recognized the suspicious, defensive, unreasoning creature that on occasion burst from beneath her delicate surface. Nor the weeping, broken one.

But always she would rally, come back to herself, beg him not to leave her somewhere billeted apart from him, love him passionately, sweetly, until he lost all reason and caved to her pleas.

Then had come the stresses of the campaign, the journey from Albany to Fort Edward, then to Fort William Henry, Heledd scrubbing laundry for the regiment, ruining her lovely hands to earn her ration. Brittle smiles. Assurances. Clinging to stability by her broken fingernails while his dread for her deepened, a slow poison taking hold.

Then she’d told him: she was again with child. After an early loss in the first months of their marriage, she’d waited long before informing him. By then they were out of Albany, heading into wilderness, she once more refusing to be left behind. Would that the babe had waited for this promised safe passage to Fort Edward. Maybe then . . .

How long shall I take counsel in my soul, having sorrow in my heart ?

Why standest thou afar off, O Lord?

Providence had abandoned him. He alone must find the words to land what might be the final blow for Heledd, and he’d rather have stripped himself naked to face a gauntlet of Montcalm’s Indians.

Shaking now, Reginald started for the stuffy timbered room where his wife had given birth—but was soon again halted, this time by sight of a woman. She lay in an alcove off the casemate’s main passage. He might have overlooked her had not two ensigns been coming from thence sup- porting a third between them, dressed in bloodied linen. They muttered their sirs and shuffled toward the sunlit parade ground, leaving Reginald to peer within.

The alcove was dimly lantern-lit. Disheveled, malodorous pallets lined the walls, all vacated except for the one upon which the woman lay. A trade-cloth tunic and deerskin skirt edged with tattered fringe covered her slender frame. Her fair sleeping face was young, the thick braid fallen across her shoulder blond. No bandages or blood marked any injury. Reginald wondered at her presence until he saw beside her on the pallet a bundle much like the one he carried, save that it emitted soft kittenish mewls. Sounds his son would never make again.

He remembered the woman then. She’d been brought in by scouts just before Montcalm’s forces descended and the siege began, liberated from a band of Indians a mile from the fort. For weeks such bands had streamed in from the west, tribes from the mountains and the lake country beyond, joining Montcalm’s forces at Fort Carillon.

How long this white woman had been a captive of the savages there was no telling. She’d no civilized speech according to a scout who had claimed to understand the few words she’d uttered. One of the Iroquois dialects. She’d been big with child when they brought her in. Reginald vaguely recalled one of the women assisting Heledd telling him she’d gone into labor shortly before his wife.

Heledd’s travail had been voluble, even with the pound and crash of mortars above their heads. But he hadn’t heard this woman cry out. Had she survived it?

He looked along the corridor. Voices rose from deeper in the case- mate, distracted with evacuating the wounded. Holding his dead son, Reginald Aubrey stepped into the alcove and bent a knee.

The woman’s chest rose with breath, though her skin was ashen. A heap of blood-soaked linen shoved against the log wall attested to the cause. He started to wake her, thinking to see if she knew the fort had fallen — could he make himself understood. That was when he realized. The bundle beside her contained not a baby, but babies. One had just kicked aside the covering to bare two small faces, two pairs of shoulders.

Reginald glanced round, half expecting another woman to appear, come to claim one of the babes as her own. They couldn’t both belong to this woman. They were as different as two newborns could be except — a peek beneath the blanket told him — both were male.

That was where resemblance ended, at least in that dimness. For while the infant on the left had a head of black hair and skin that foretold a tawny shade, the one on the right, capped in wisps of blond, was as fair and pink as Reginald’s dead son.

The ringing in Reginald’s head had become a roar as he bent over Heledd to wake her. His heart battered the walls of his chest like a thirty-two pounder set at point-blank range, waging internal war. Despite his mistakes with Heledd, he’d still considered himself a good man. An honorable man. For five-and-twenty years he’d had no indisputable cause to doubt it. Until now.

How could he do this thing?

With a groan, he backed from his wife. He would set this right, re- turn things as the Almighty had — for whatever inscrutable reason — caused them to be. There was time to undo what ought never to have entered his thoughts.

Only there wasn’t.

Heledd’s eyes blinked open. A slender, reddened hand felt for the infant gone from her side. With a cry she heaved up from the cot, hair flowing dark across her crumpled shift.

“Where is he? My baby!” Panic pinched her voice, twisted her fine- boned face into a sharp mask.

Reginald’s heart broke its pummeling rhythm, swelling with love, aching with shame. “He’s here. I have him here.”

With grasping hands Heledd took the swaddled babe. The child’s features were scrunching to cry, but the instant it settled in Heledd’s embrace, it calmed.

Reginald’s hands shook as his wife stared at the child in her arms. She would know. Of course she would. What mother wouldn’t? In another heartbeat she would raise those brown eyes that had claimed his heart, sear him with accusation, unleash the darkness that he knew bedeviled her, and he’d have lost more than a fort and a son and his honor this day.

Heledd’s narrow shoulders heaved. Like a mirror of the babe’s, her face calmed, softening in a manner Reginald had never seen. Not even on their wedding day when she’d looked at him as though he’d lit the moon. It was as though, in the face of the child in her arms, she’d found her sun.

“Oh . . . it is well he looks. When I saw him before I thought — was his color not a bit sickly? But do you look at him now, Reginald. Our son is beautiful.” With a bubble of laughter she raised her face to him, joy shining from her porcelain features, her beautiful eyes alight in their bruised hollows.

He couldn’t see the darkness.

For a fleeting moment Reginald was glad for the thing he had done. “He is —” The catch in his voice might have been for reasons purer than the truth. He was beautiful, Heledd. As I lay him beside the dark child, I saw he had your eyes . . . my mouth . . . and I think my father’s nose.

“Major?” a hurried voice hailed from the doorway. “Ye’ve but moments to be on the parade ground, sir.”

Reginald nodded without looking to see who spoke. Grief and guilt swallowed whole his gladness.

For mine iniquities are gone over mine head . . . neither is there any rest in my bones because of my sin —

As footsteps hurried away, he tore through his soul for refuge, even the most tenuous — and found it in Heledd and what he must now do to see her safe across fifteen miles of howling wilderness. He clenched his hands to stop their shaking. “Quickly,” he told his wife. “Let me help you dress.”

Heledd wrenched her gaze from the babe to echo vaguely, “Dress?” “Aye. You must rise, and I am sorry for it, but we have lost this ground.

We’re returning to Fort Edward.”

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)